Note: This is the first chapter in the book and was submitted as an independent study project during my undergraduate studies at Worcester State University. Usage of MLA style is therefore present in the work, though I have not included a citations list. The book will be finished over the summer of 2018 and is intended to be published in 2018/2019.

Copyright 2018 by John J. Griffin

The Green Family at Green Hill in 1861 L-R: Lydia Plimpton Green, John Plimpton Green, Lucy Merriam Green, Samuel Fisk Green, William Elijah Green, Martin Green, Julia Elizabeth Green, William Nelson Green, Mary Ruggles Green, Andrew Haswell Green, Oilver Bourne Green;

A Sample Chapter of

Virtue is Always Green: The Life and Legacy of Andrew Haswell Green.

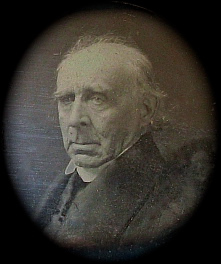

Andrew Haswell Green

The story of every great individual starts at the beginning and in Andrew Haswell Green’s case, this means going back more than a century before he was born. However, while Green’s family can trace their lineage back to when their family first arrived in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, no evidence has ever been uncovered which tells the stories of the Green family back in their native home of England. This led Andrew to sarcastically comment on the subject when he addressed a gathering commemorating the 150th anniversary of the church which his great-grandfather built in Leicester, Massachusetts. Andrew stated:

“Of all this we really know but very little; it is chiefly guesswork. But on the other hand, this we do know, that our emigrant was named Thomas Green, and that he lived at the same time with the illustrious persons whom I have mentioned. To bring the best proof we have of kinship with them, which it must be admitted is not very conclusive, I may mention that Benjamin Green was one of the subscribing witnesses to that agreement by which, for five pounds, the great Milton, poet, statesman, scholar, transferred his immortal epic to the printer, Symons. And this further history affirms, that Thomas Green was a relative of, and fellow comedian with, William Shakespeare, and that Shakespeare’s father possessed an estate, known as Green Hill (The Founding Exercises 72).”

What is known is that the Green family’s story starts with the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, with some of Andrew’s ancestors being passengers aboard the Mayflower. However, the first member of the Green family to arrive, was a man hailing from England named Thomas Greene, arriving in 1636 when he was approximately thirty years old. By 1651, he had a wife and five children, and had settled on a farm in Malden, Massachusetts, in an area which is now part of the towns of Melrose and Wakefield. Five more children would be born to the couple while residing in Malden, further branching out their descendants into the newly forming nation.

Thomas Greene was a well-respected member of his community, regularly called upon to serve as a selectman for the town or as a juror. His oldest son, Thomas Jr., ends up marrying Rebecca Hills, the daughter of the prominent lawyer Joseph Hills, and his wife Rose Dunster, the sister of the first president of Harvard. The couple gives birth to five children, one of whom was their son, Samuel. Samuel Green would grow up in Malden and go on to marry Elizabeth Upham, a descendant of the branch of the Upham family who fought against the Narragansetts during King Philip’s War. Elizabeth gave birth to eight children, the fourth being their son Thomas, the 3rd, born in Malden on October 5, 1670. It should be noted that while Samuel Green is commonly referred to as Capt. Samuel Green in most sources, a thorough search has uncovered no evidence of his service or how he obtained the rank of captain.

Nonetheless, in February of either 1713 or 1714, the General Court of Massachusetts grants permission to Capt. Samuel Green and Col. William Dudley, of Malden, to settle the town of Leicester. In 1717, Capt. Green sets out for Leicester with his family to become the town’s first residents.

Captain Samuel Green’s estate in Leicester was measured to be at 180 acres, bordered by the French River, upon which he built both a saw-mill and grist-mill. Additionally, he builds a garrison fort on the property to afford a means to defend the townspeople from hostilities. Like his father and grandfather, he was a prominent member of his community, then known as Strawberry Hill, serving the town in many capacities. He moderated the first town meeting, as well as serving as the first selectman and grand juror of the town. Capt. Green would serve in those capacities until he died in 1736, at the age of sixty-five.

Capt. Green’s young son Thomas would have been nearly eighteen when he moved to Leicester with his family in the summer of 1717. After driving their herd of cattle to Leicester from Malden, Capt. Green left his son Thomas to tend to the animals while he made his way back to Malden, promising to return shortly. Shortly after, Thomas began to grow sick with a fever and was unable to take care of himself. Taking refuge beneath a stone ledge that created a kind of cave, Thomas drank water from the nearby stream, which he would crawl to each day from his nearby shelter. He would find nourishment by tying a calf to a nearby tree and drinking milk from its mother’s udders when she came over to nurture her calf every few hours. Eventually, some of Thomas’ former neighbors from Malden happened upon him, moving their cattle from Malden to Leicester as well. They apparently did nothing to help him, claiming that they could not afford to, causing Thomas to bitterly weep at their unkindness. Upon returning to Malden, they informed Captain Green of his son’s condition and he immediately set out on horseback to rescue his son.

During the first years that Thomas lived in Leicester, two English surgeons who had escaped from the service of Spanish pirates, sought amnesty and ended up at Capt. Green’s farm in Leicester. While housed there, the two surgeons give young Thomas an education in medicine and he subsequently becomes the first of at least five generations of physicians in the Green family. Additionally, he is rumored to have gained some medical advice from local Nipmuck natives who instructed him in identifying native plants and their medicinal uses.

Thomas Green M.D. eventually becomes known as Reverend Thomas Green M.D., after forming the first Baptist congregation in Leicester, personally financing and building the first Baptist church in the town in 1738. Additional evidence shows that he was also instrumental in the founding of the First Baptist Church in Sutton back in September of 1735. It is said that during the course of his ministry, Rev. Green baptized at least a thousand people. Though this is evident of his effectiveness as a minister, few written records exist that detail his work as a minister. It was well known in the community that while Rev. Green was preaching in the church on Sundays, he kept a pot of food warming on the stove, ready to provide a warm meal to any of his congregants in need. Besides being dedicated to his career in medicine and to his ministry, Rev. Green also found time to take on students, teaching medicine to a total of more than a hundred and twenty pupils in his career. Of Rev. Green, it was said that he “…lived three lives and did the work of three men in one. He was a man of business, active, energetic and successful (Swett Green 6).” He was renowned for his surgical skills and remembered, at the time of his death in August of 1773, as being “a physician distinguished for his success in the healing art (The Founding Exercises 35).” Over time, Rev. Green’s prominence gives rise to the trend of referring to the section of Leicester, which the Green family settled, as Greenville. He marries Martha Lynde, the daughter of Captain John Lynde and they have seven children, their fifth child named John, was born in Leicester on August 14, 1736.

Rev. Green was also have known to have made a great deal of his money in real estate and according to records kept at the Registry of Deeds in Worcester, between 1735 and 1773, he appears as a grantee fifty-seven times, and as a grantor fifty-nine times. One of Rev. Green’s most important investments was his purchase of a property in Worcester on May 28, 1754. The tract of land is purchased from Thomas Adams for three hundred and thirty pounds, six-eights of which he paid for at the time of sale. The property which Rev. Green purchased was not far from the area visited by a committee in 1668, who determined that the region would be a suitable location for a village. Six years after, the first settlers of Quinsigamond Plantation arrive and make the first of three attempts to establish a village in the region. Over forty years later, when the third settlement has been permanently established, Aaron Adams of Sudbury, his brother Thomas, and several other individuals, agree to pool their funds and purchase the land around what is now Green Hill. They buy an eight-square mile plot of acreage intended to be used as a hunting ground, just as the region had been used by a nearby Nipmuck village for centuries. Five years after, Adams has obtained two more tracts of this land, equaling eighty-one acres in all, and he builds his farm on the northern side of what would come to be known as Millstone Hill. Some of the evidence of his farm is still present in the area, though evidence of cellar holes was destroyed by an expansion of the Green Hill Golf Course in 2017.

Rev. Green’s intention in purchasing the land was to provide his son John with a home which would be close to the family estate in Leicester, but far from the influence of the taverns in the center of Worcester. Though this was unnecessary, as he abstained from drinking, just as his father did, John Green moves to Green Hill in 1757. By 1782, Green acquires the southern portion of Millstone Hill, greatly expanding his estate, and in 1790, builds the house which several generations of Greens would call home.

Besides his choosing to abstain from drinking, Dr. John Green followed in his father in another way, choosing to be the second in a line of medical practitioners in the family. Dr. Green was famously known for the vigilant way in which he kept watch at the bedside of his patients, day or night. Like his father, he was known for being extremely tall and largely framed. It is said that when Dr. John and Rev. Thomas’ remains were transferred to Rural Cemetery in Worcester, the size of their coffins was remarked upon by those who witnessed the event. His stature also was discussed in the stories told by those who recalled seeing him quickly riding through the streets of Worcester to the home of his patients on horseback, with a half-dozen medical students, and a pack of hounds, chasing after him wherever he went. Legend has it that on one occasion, Dr. Green took the locust switch that he had used as a riding crop and firmly planted it into the ground outside of the family home. That switch took root and for many years, a grand tree grew on the spot upon which he stuck it in the soil.

Timothy Ruggles

During the Revolutionary War, Dr. Green serves as a member of the Committee of Safety and Correspondence and as one of four representatives to the General Court from 1777 to 1782, additionally serving as a town selectman in 1780. Dr. Green would marry twice, his second wife being Mary Ruggles, the daughter of General Timothy Ruggles, a military leader who served during the French & Indian War. Additionally, General Ruggles is a descendant of John Tilley, one of the Green family’s connections to the Mayflower pilgrims.

It is the Green family’s connection to the Ruggles family which merits discussing a notable piece of history. It involves the story of Bathsheba Spooner, the first woman executed in what would become the United States. Like Bathsheba Ruggles, her husband Joshua Spooner came from a prestigious, wealthy family and together they lived in a mansion in Brookfield, Massachusetts. The short version of this tale is that during the Revolutionary War, a young solider named Ezra Ross was taken into the Spooner home after becoming seriously ill while traveling through the area with his regiment. Bathsheba nurses him back to health and they eventually fall for one another, inspiring a plot to kill her husband so she can be with Ross. Two other soldiers are brought in on the plot and the three soldiers end up killing Bathsheba’s husband. A couple days later, two of the soldiers get drunk while in Worcester and are showing off the silver buckles which they stole from Joshua Spooner. The murder is uncovered and after convicted, all four are executed before a crowd of five thousand onlookers in what is now known as Washington Square.

A notable bit of history, found in Caleb Wall’s Reminiscences of Worcester, and orally related to me by one of the Green family descendants, is that Bathsheba’s body was buried in the garden behind the Green family home. As she was connected to their family through Dr. John Green’s wife, Mary, the Greens chose to quietly bury their family member on their property, as she likely would not have found a proper place to be buried elsewhere due to her crime. Thus, what remains of her body still rests atop Green Hill, very close to where the mansion was once located.

With Mary Ruggles, Dr. John Green has ten children, the oldest being his namesake, John. John the 2nd not only carries on the family tradition of bearing the same name and making a living as a doctor, but additionally names his son John, who also chooses to go into medicine. However, Mary and Dr. John Sr.’s seventh child was William Elijah Green, born in 1777 at Green Hill in the same room in which he would later die in, at the age of 88. William Elijah was a member of the Class of 1798 at Brown University, after which he studies law with Judge Edward Bangs of Worcester. He begins his practice in the neighboring town of Grafton, though eventually pursuing his profession in Worcester. At the death of his father in 1799, William Elijah inherits the two-hundred-acre family estate and decides to retire from law in order to oversee the family farm. The estate by now had been converted into a working farm, with produce being sold at local markets, bringing in income for the family. Purchasing more land to add to the size of the family farm and estate, William Elijah buys fifty acres of the neighboring Crawford Farm. He then dams up the nearby brook and creates a small pond in the wetlands area. This would end up becoming Green Hill Pond, still a major, but heavily polluted, feature in the park.

Another land purchase increases the size of the family estate, this time the northern portion of Millstone Hill is purchased. There is an interesting case which is connected to the quarry on Millstone Hill, from which Worcester’s citizens had historically gathered stone for foundations for their homes, long before the Greens settled at Green Hill. After William Elijah purchases the land, he decides to sue in order to stop people from gathering stone from his land. Oddly enough, William Elijah lost the case, effectively permitting the people of Worcester to trespass on his property and literally take his land.

William Elijah would marry four times and have eleven children. His first wife, Lucy

William Elijah Green

Merriam, would give birth to one of these children, also named Lucy. William Elijah’s third wife was Julia Plimpton, the daughter of Oliver Plimpton, a solider in the Revolutionary War, and Lydia Fiske, the daughter of Daniel Fiske who served on the Massachusetts General Court during the Revolution. With Julia being the mother of nine of those children, their fifth child, born on October 6, 1820 was a boy who they named Andrew Haswell Green.

Andrew had a loving father in William Elijah Green, according to John Foord. Speaking of William Elijah, he wrote:

“The father was a man of fine personal presence, had a constitutional geniality of disposition and exercised a liberal hospitality. With his boys, he was a comrade and companion, a participant in their pleasures and a helper in their studies. His literary tastes were exceptionally comprehensive, and he had a breadth of culture not commonly found in a country lawyer of that time, even in Massachusetts. The Puritan ideals of faith and of life seem to have sat somewhat loosely on William E. Green, and the mere joy of living possessed him in a way that would have brought him reproof from the spiritual fathers of the community in sterner times. Boys brought up under the influence of such a man were likely to have all the faculties of mind and body well developed, to detest falsehood and to scorn pretentious self-importance (pp 5-6).”

During this time, the population of Worcester was generally located in the center of the town and Green Hill would have been considered to be on the far outreaches of its borders. The Greens had no nearby neighbors and assumedly, their sense of isolation would certainly be increased after being snowed in by a classic New England blizzard. This element not only made the family more resilient, but emotionally connected to one another as well. It was said that they were a highly principled family, intellectually minded and given to exchanges of views which would be heartily and frankly discussed. Their tendencies towards intellectuality was tempered with a puritanical religious devotion that was deeply ingrained within the fabric of that family.

Andrew was particularly fond of the family estate. Writing about his early years at Green Hill, he wrote, “It is delightful once more to be at a place that I can call home; everything that I see reminds me of my childhood which has passed away and taken with it many of the pleasures of life (Foord 7).” The first fifteen years of Andrew’s life would be spent upon Green Hill and he would become intimately acquainted with every inch of the family estate, of which it was said that Andrew “…knew every tree by name, and loved every feature of its varying landscape (Foord 7).” Andrew freely roamed through this picturesque landscape, it later becoming a sanctuary for Green when he wished to escape the fast pace of New York. It was here, on his family’s picturesque estate, that Andrew grew to love nature and formed an interest in landscaping which factored into his planning of Central Park. Writing about the family home, Andrew described it as being

“…not far from the city of Worcester, a plain wooden dwelling, two storied but low ceilings, of ample length and breadth, and anchored by a chimney of needless proportions. It stood by on a by-road or land, which was but little frequented. About the premises could be seen evidence of taste struggling for more emphatic manifestation, but confined by imperative demands upon a limited treasury (Swett Green 7).”

In describing Andrew’s love for his home, he notably speaks even of the land itself in loving terms, fondly admiring each of its features, each being a connection to a memory of Green’s youth. Far from being bored there, he described the family home as being “…a heterogeneous museum of relics, affording inexhaustible amusement (Swett Green 7)” and noted that there was a library which was “rather scant, but of standard works, elevating, refining and well read (Swett Green 7).”

A notable piece of history relating to the mansion has to do with an alleged tunnel which extended to the west from the mansion. The story is that it was built to escape attacks from local Native Americans, though it was later rumored to have been used as a stop on the Underground Railroad. According to a report prepared for the City Manager of Worcester’s Office in 1979, the brick-lined tunnel still exists, but has since been filled in. If the sources for this story are accurate, there is a very high chance that the tunnel was used to aid escaping slaves from the South, at or around the time that Andrew Haswell Green is living at Green Hill.

Andrew was educated in a public school and tutored by a man named Charles Thurber. Under Thurber’s tutelage, Andrew studied subjects like mathematics and grammar, while additionally learning Greek and Latin. During the warmer months, Andrew enjoys working on the family farm and his journals from this period discuss the duties he performed. These would include building a chicken coop, ploughing the fields, harvesting corn, mowing and raking hay, picking and storing apples, and preparing produce to be sold at the local market. When Andrew was not performing these chores, he would enjoy hunting in the nearby woods, fishing in the ponds and lakes in the area, and gathering nuts with his brothers.

At the age of fifteen, Andrew begins to consider his career path. Initially, Andrew was hoping to attend the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, but his father could not afford to send Andrew to college, and so Andrew begins to hatch his plans for the future. He decides to leave Green Hill and move to New York where his sisters Lucy and Mary have established a school for young women. Andrew and his sister Lucy leave Worcester by stagecoach for Providence, boarding a steamboat there bound for New York, arriving in the city on April 30, 1835.

The population of New York in 1835 is around 250,000 people, no doubt being an overwhelming world for Andrew, significantly different than the one he left behind at Green Hill. Unlike the New York we know of today, the city was over by wild pigs and other animals which roamed through the shack-lined streets, many of which were still only dirt roads and did not fully run into the northern end of Manhattan. Andrew sets out to find a job and shortly after, is employed as an errand boy for Hinsdale and Atkins, earning a salary of $50 a year with board. By February of 1836, Andrew has taken a job as a clerk at Lee, Savage, and Company, a wholesale cloth merchant and importing company.

During this period, Green is often writing letters to a close friend of his named Samuel G. Arnold who is attending college in Providence. Exchanging letters often, the both competitively boast of the numerous ships which they have seen coming and going out of the ports in their respective cities. Details which include the name of the ship, its port of origin, and its destination were ones which Andrew found fascinating enough to meticulously record and share with his friend, equally enjoying receiving the same details from Arnold, pertaining to the ships which arrived in Providence. This would begin Andrew’s life-long love for statistics and meticulously recording them. Along with this exchange of details came the boasts of each having the more prominent port in the country. In a letter he sends to Arnold in July of 1837, Andrew backs up his claim by including an article he has discovered which states that New York had become one of America’s significantly important shipping ports.

Although he held the Green family trait of having a strong build and constitution, Andrew intermittently suffered from bad health. During such an occasion, he decides to leave New York and return to Green Hill where he recuperates. While at Green Hill, he reads a letter which Andrew’s sister Lucy had sent from New York to her family. In the letter, Lucy wrote that she felt that Andrew was not living up to her expectations of him, that he had not fully been attentive enough to his studies, and was never going to become a sophisticated individual unless he changes his lack of interest in reading. Andrew seems to be affected by this and records the incident in his journal, immediately after which he sets out to make his sister proud of him by becoming more studious. By July 10th, he begins to earnestly educate himself by reading historical works and then moves on to reading classical literature, including the works of Virgil. This is the start of Andrew’s passion for literature and for education, the beginning of his becoming a well-educated and highly-refined individual, with an appreciation for the liberal arts.

After spending a couple months at Green Hill, Andrew returns to New York and resumes his job at Lee, Savage, & Co. He begins to show a firmer sense of dedication to his position in this period, deciding to force himself to get to bed no later than 10:00pm, so that he could arrive at work as early as 6:00am. Even if he does decide to have breakfast before he leaves home, he still arrives no later than 8:00am, the same of which could not be said about his fellow employees. Andrew is tasked with noting the arrival and departure of the various ships who visit the port by way of keeping track of their movements on numerous slips of paper, each recording the details of each vessel’s business. He eventually impresses his boss enough that by 1837, Andrew is made a member of the company’s counting house where he keeps track of their transactions. In his journals, Andrew writes that while he enjoys working for the company, he does not enjoy bookkeeping the business’ accounts.

His journal entries in this period display Andrew as having an extreme sense of

Andrew H. Green in his later years

conscientiousness, when meticulously recording details of personal expenses and such. Exhibiting an almost prudish side to him, he also frankly speaks of how he feels that society lacks moral standards pertaining to how members of the opposite sex behave towards one another in public. Andrew also reveals moments of self-chastising in an entry he makes about the guilt he feels for making a mistake at work when his account comes up ten cents short. The incident increases his resolve to be more meticulously attentive to the details of his work. Additionally, he expresses regret on another occasion when he accidentally sends a letter to a friend with postage due. Andrew characterizes his action as being troublesome to his conscience and that he felt that it would be impossible to fully repay his friend for the inconvenience of his actions. Andrew’s tendency towards regret emerges in another journal entry which records an instance where he is upset over the fact that on December 29, 1838, he drank two glasses of wine. For a man who only drank a glass of wine a year at the most, which was true even until the end of his life, this was a significant event, one which he sincerely expresses great remorse over.

Though highly virtuous, Andrew’s interpretation of religious doctrine was extremely liberal, gaining this trait from his father. At the age of seventeen, he is drawn towards Unitarianism, though he later expresses an inclination towards Evangelical Puritanism, firm in his observation of Sunday as being the sabbath. He later has a change of heart, recording in his journal that he feels it is unfair to all of society to designate that Sunday should be universally observed as the sabbath day purely for his own reasons. At the age of nineteen, he experiences a deeply turbulent sense of spiritual conflict which he resolves by deciding to become a born-again Christian.

Andrew would continue to attend church regularly, as well as going to prayer meetings during the week. When he was not working or at church services, Andrew would often be found in the company of his cousin Timothy R. Green, who also lived in New York. Other activities which he records engaging in include taking in a play at Niblo’s Garden, playing cards, or attending a dance party. However, it is Andrew’s interest in religion which inspires him to briefly become a Sunday School teacher. He attempts to help the less fortunate children in his neighborhood to forge a spiritual relationship with God, but he is unsuccessful in his endeavor for whatever reason.

Andrew’s interest in politics only became more prevalent as an adult. Early on, his journal entries briefly express a sympathy for the conservative Whig party, though as he grew older, he would fully embrace the Democratic party’s agenda. Nonetheless, Andrew was not shy about speaking up when he did not agree with his party’s stance.

By the end of 1837, Andrew has become disillusioned with the idea of succeeding in the commercial shipping industry and begins to think about his next move. Lee, Savage & Co. is dissolved in August of 1839, with Green and Savage remaining on good terms. For a brief time after, he is employed by linen importing firm of Wood, Johnson and Burrit. Andrew then decides to take a trip back to Green Hill where he spends the next year planning out what to do next. He starts and ends his return home with a visit to Samuel Arnold who is still in Providence. During his time back at Green Hill, Andrew is found working in the fields most of the season, though in the winter he spends most of his time in the library at the American Antiquarian Society. Andrew also starts to become aware of his own mortality. This happens after having the bouts of ill health over the past few years and so Andrew decides to draw up a will for himself. Notably, Andrew is careful enough to include in the document that he owes his sisters Lucy and Mary $2.70 which he borrowed from them on October 7, 1839, only paying them back $1.16. It is Green’s desire to meticulously record details, coupled with his innate sense of honesty and piety, is what becomes a defining feature of his legacy.

While at home, Green forms a friendship with a mentor named Elihu Burritt, apparently known to Andrew as the “Learned Blacksmith.” Burritt takes him under his wing and teaches Andrew how to speak and read Icelandic, while encouraging Andrew’s pursuit of the Hebrew language by gifting him a Hebrew-English dictionary and a Bible written in Hebrew. This awakens something in Andrew. Like his experience with reading the critical comments in his sister Lucy’s letter, Andrew’s time with Burritt awakens his interest in linguistic and ethnological studies.

Andrew returns to New York on February 3, 1841 but is unable to find employment outside of doing tasks for the auctioneer Simeon Draper. Additionally, he does not care much for the job as he is tasked with staying up late at night, making sales for the company. He also suffered from poor eyesight, and so working at night was not advantageous for Andrew. Throughout 1841, Andrew’s zealousness for religion reemerges and on his 21st birthday, he is baptized at the Battery by Rev. Ogilby, a Professor at the Theological Seminary on 21st Street. Among the gathered witnesses at his baptism were his sisters Lucy and Julia.

A few weeks after, Green meets a friend of the family named William Burnley. Burnley was looking to make a quick profit in the sugar industry and was intent on purchasing a plantation in Trinidad. Andrew was asked to run the venture, which he heartily accepts. On November 3rd, Andrew sets sail for Barbados, a trip which would take over three weeks, during two of which, the ship experienced violent storms. While at sea, he begins to earnestly acquaint himself with how to run the plantation, located at Tacarigua. He investigates how to properly grow the cane, types of soil and fertilizer to use, and then how to process the cane into molasses or sugar. His studies certainly helped him to do his job well, though he was unable to successfully apply the innovations which he realized in the course of his studies.

In January of 1842, Andrew is preparing for the “grinding season,” when the harvested cane will be prepared for processing in the “boiling-house.” Right before the season starts, the workers have their pay cut from five bits to three bits per task, and so there was a rising sense of discontent among the workers. Andrew’s reaction to this is unusual in that he is dismayed at how the workers protest this decision. He feels that the only way that the workers are going to be able to stop being exploited in this fashion is if they choose to be educated. By being educated, they will have the tools which will allow them to work for themselves, becoming more self-sufficient, and less dependent on the plantation owners who are only interested in making a quick profit. While Andrew understands that these plantation owners are only businessmen and that their concerns are only short-termed, he cannot help but to view them as being selfish and ignoring the long-term effects of these types of operations on the population.

The workers who Andrew supervise are majorly either freed slaves or the descendants of slaves who were brought here to the Americas from Africa. In his journal, Green muses over whether or not Abolitionism is a good idea. He unfortunately reasons this as being because they have not had a Christian-based education which has impeded their desire to do hard work without being persuaded. While he may not have believed that the Africans had the necessary education that would increase their desire to be productive and self-sufficient, he is willing to educate them and additionally felt that the Africans were able to be educated. While these examples are tainted by Green’s prejudices, it is probable that he had his heart in the right place, even if his understanding of the situation was influenced by the prejudices of his day. It also must be remembered that the Green family home was a stop on the Underground Railroad so whatever sentiments he may have expressed in his journal may not have been entirely meant to be racist.

Regardless, Andrew took it upon himself to educate the plantation workers and decides to set up a Sunday School to teach them about Christianity. He takes possession of an unfinished home on the island and teaches his first class that Sunday. The number of attendees starts off small before it peaks, before attendance quickly dies off after a number of weeks. By February 6th, no one shows up for Sunday School. Nonetheless, Andrew is persistent, gaining a few allies along the way. In April, he decides to solely focus on teaching the children. As the adults are illiterate, he feels that he can more easily instruct the children by introducing them to the Bible at an early age. The class grows to about fifteen children but the results are mixed. Without the support of a local clergyman, or the other planters, the venture is extremely difficult, but he doesn’t give up. However, by August, Andrew is forced to close the school when the Spanish owners of the house he had been using, return to the island and reclaim their property.

Andrew continues working long hours in the boiling house despite not feeling as strong as he would like to feel. By the end of the season, he is exhausted but continues working in the fields, living in a shed whose floor measured eight feet by eight feet, and having bare shingles for a roof. Soon, he grows tired of these conditions and decides to make his way back to New York. On September 9th, he boards the Hummingbird bound for Baltimore, eventually arriving in New York on the 30th of September. Fresh from Trinidad, Andrew is without a plan and unemployed. Without many options, and having tried his hand at a number of careers, he decides to follow in his father’s footsteps and begin the process of becoming a law student.

To Be Continued